Interview John Divola

John divola

INTERVIEW BY Alexander Basile for the plantation journal

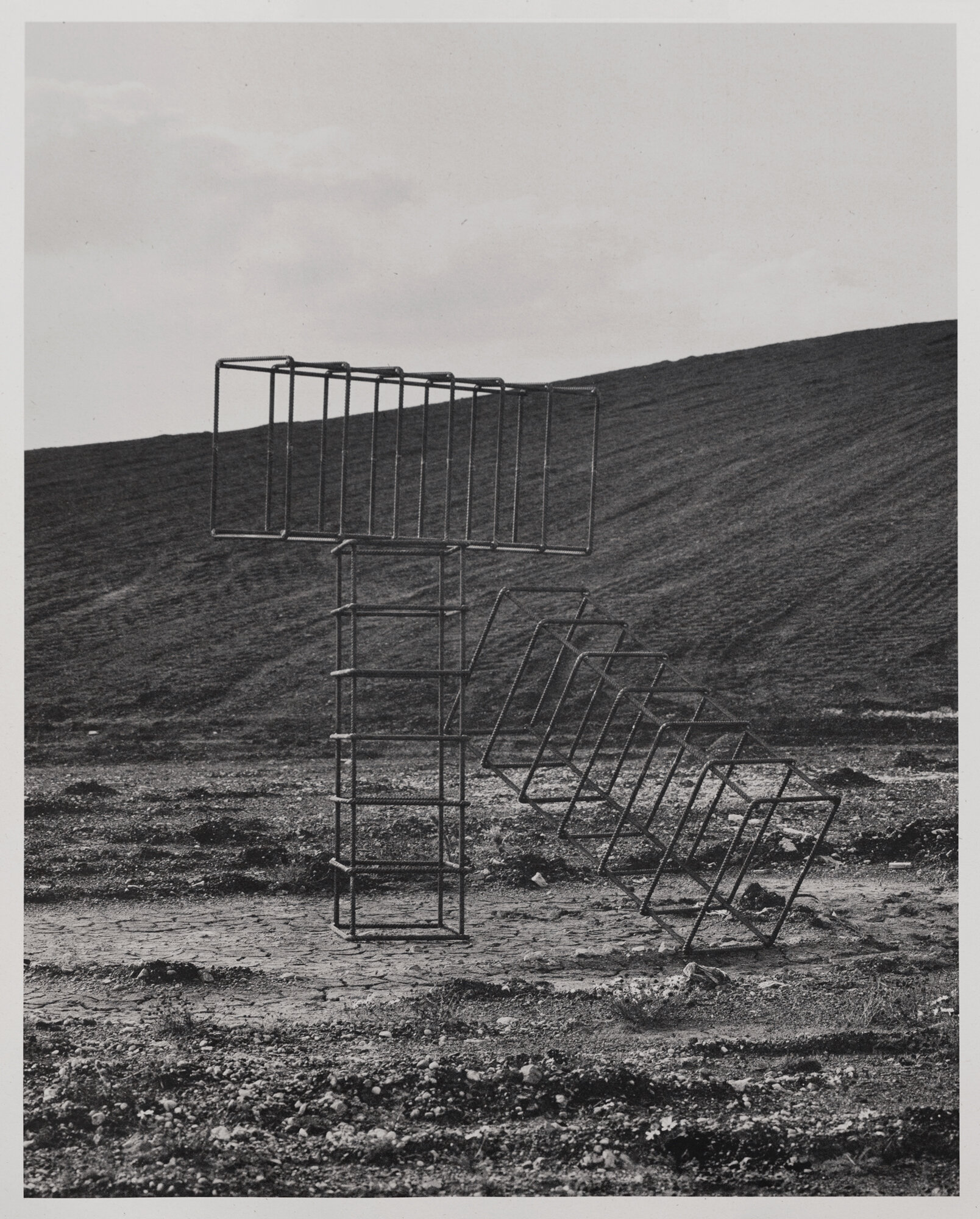

Alexander Basile (AB): Looking back at your series Vandalism and Zuma it feels like a young artist / photographer could have shot them more recently. For me it’s fascinating to see your body of work in comparison to other artists from the 1970s such as Stephen Shore with his color photography or Bernd and Hilla Becher with their typologies. And then there’s your series Vandalism and Zuma with their totally different approach to photography. Creating this sculptural moment using the camera. Nowadays a lot of young artists work like this using photography to finish a sculptural work or let it emerge through photography. How did you start out?

John Divola (JD): That body of work, Vandalism Series, was made between 1973 - 1975. The Zuma Series was 1977 & 78 a couple of years after my graduate studies at UCLA. I started out in photography studying at the California State University, Northridge, a fairly pure photography program, and then went to UCLA for graduate school where photography was more integrated with a broader discourse of the visual arts. At that time if you went to the East coast of US, the primary discourse of fine art photography focused mainly on people like Walker Evans. The claim for Walker Evans was that he kind of got out of the way, meaning that the work wasn't contaminated by ego and pictorial subjectivity but it was more of a direct representation of the subject. So this notion of describing the social reality in front of you purely and completely, without influencing it in some way, is what was valorized in photography of that period. And the Becher’s, who you also mentioned, are almost the highest manifestation of unmediated reference. They really do get out of the way in terms of photographing in flat light so that shadows don't interfere with the reading of the physical object or the industrial architecture that they are describing. Although in their work there was a definite interest in those structure as objects with “sculptural” attributes. So that was the primary discourse in the East coast but I was on the West coast where as an undergraduate the guy I was studying with in the photography program at Northridge, Ed Sievers, had been a student of Harry Callahan whose work least comfortably fits that idea. When I went on to UCLA and worked with Robert Heinecken, I was introduced to the broader discourse of contemporary art. However, my experiences of art were very distanced since at that time in LA we didn't have a lot of galleries. There wasn’t a museum of contemporary art so I never saw any original art works, only reproductions in magazines or as slide projections on walls. I was only seeing pictures of art not actual art objects.

AB: So what was your relationship with photography?

JD: Initially, I was interested in the fact that I was moving through a landscape with this machine and I was making these impressions of the people, places and buildings that were in front of me. But at that time people tended to assume that this was a social commentary on the subject. I was far more interested in the photographs as artifacts or remnants of a process or personal engagement. I began looking for a way of working where my process or activity was an inescapable aspect of content. So, I found myself painting in abandoned houses. I was initially working with a modernist vocabulary. I used corners where I thought ‘OK, I’ve got this three dimensional space in front of me which is going to flatten into being a two dimensional surface for the photograph’ and from that I thought about what I could do to play with the reading of the space. If I put in evenly spaced dots across the surface, they would come together to form a gestalt on the surface of the image. It was those sorts of components that I was playing with. I was no more interested in my painting than what was already present, broken glass on the floor or holes kicked in walls. The painting was a way to activate the space and implicate my engagement with the space

AB: So the possibilities of using a camera offered a way to interact with the space? When I first saw your work in 1998 I really felt that you were pushing the borders of what photography could be. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben talks about the term 'profanation' and I always liked this idea. By this profanation of the camera, with all that it meant and how it should be used, you were able to create something light and playful but still very rich in content.

JD: I called it 'The Vandalism Series' not because I thought I was vandalizing the house but I thought I was vandalizing a tradition in photography. At that time photographers would widen the negative carriers so they could print a black border around their negatives to prove that they had used the entire area of the image when they made the prints. They would try and emphasize the integrity of the process and non-intervention with the subject. So ‘Vandalism’ was more directed towards that idea than the fact that I was literally vandalizing locations.

AB: That reminds me about an article I read recently about Reuters who had asked their photographers to only photograph in .jpg format and not use raw format anymore which goes to show they are still consumed with the issue of reality. The series 'Zuma' was shot in color and we see objects appearing. Is there a difference between these two series?

JD: When you decide to work in color you don’t just literally add color, for example painting a blue dot, but you also add color in an ephemeral sense. You can talk about how warm the light was or how much moisture was in the air. It allows you to reference the subtleties of the atmosphere that couldn't be done equivalently in a black and white image.

AB: In the wonderful book 'The Great Unreal' by Swiss artist duo Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, I see a lot of references to your early works. In general I feel that a lot of young artists these days refer to your work. Did you agree in feeling that your body of work is influencing the current discourse in contemporary photography?

JD: I have noticed that more people have become interested in this body of work in the last ten years. I have no way to know if the work is actually influencing somebody or not but I know that the approach is a very prevalent one at the moment. Saying that, I don't delude myself in the thinking that I am the only person on the planet to have come to these kinds of conclusions about how photographs operate culturally and what makes sense in terms of an approach. I think I was fairly early to adopting the perception but I have no way to value the influence or significance it has on others now.

AB: How did you define yourself back then? Did you see yourself as a photographer or as an artist?

JD: Normally when I‘ve been asked I’ve said I’m a photographer because if you say you’re an artist it generally requires giving a lot more explanation. I still think of myself as a photographer but I do also see myself as an artist. I don't see the two characterization as being mutually exclusive. When I was in graduate school I came to the conclusion that all art was fabricated to be photographed. I have retreated from that position a little but from my point of view at that time, it seemed that if anything had any kind of cultural efficacy, or consequence, it was through its subsequent representation. So with all kinds of works, sculptures, performances and conceptual artworks, they were literally being fabricated in order to be photographed. So I came to this conclusion that all of that discourse was going to be translated though some manner of photographic manifestation. That I could reference ideas about painting, sculpture, gesture and performances within that arena and without having to differentiate between them. And I even think to this today, if you are a critic and you see an original painting that you want to write about, well by the time you get to writing you’ve probably already seen it 50 times in reproductions before and after actually standing in front of it. It is not simply that it is impossible for you to differentiate the source of what constitutes your subsequent mental image of that painting. As time passes, the perceptions from direct experience and indexical representation become increasingly equivalent in memory. What is interesting is that it never occurs to us to question the literal origins of our sense of these objects. So I am still very interested in the idea around what happens to art works in our memories and the relationship between direct experience and the subsequent experience through secondary representation.

AB: John, thank you for this interview.

Find more of John Divola's work here!

John Divola (1949) is visual artist from California. He is represented by Maccarone Gallery - N.Y.C., Gallery Luisotti in Santa Monica and Laura Bartlett Gallery in London.

Alexander Basile (1981) is a German artists who works as a curator. He is the curator of the upcoming group show How Things Shouldn’t Be Done at Gallery Clement & Schneider, which will feature John Divola’s work, September 2016.