Matt Greenwood #26

COLLECTIVE 26

MATT GREENWOOD

Collective focus on the artistic process of one emerging artist; we learn about their sculptural practice and how it relates to construction, deconstruction, or both. Questions by Joanna Cresswell.

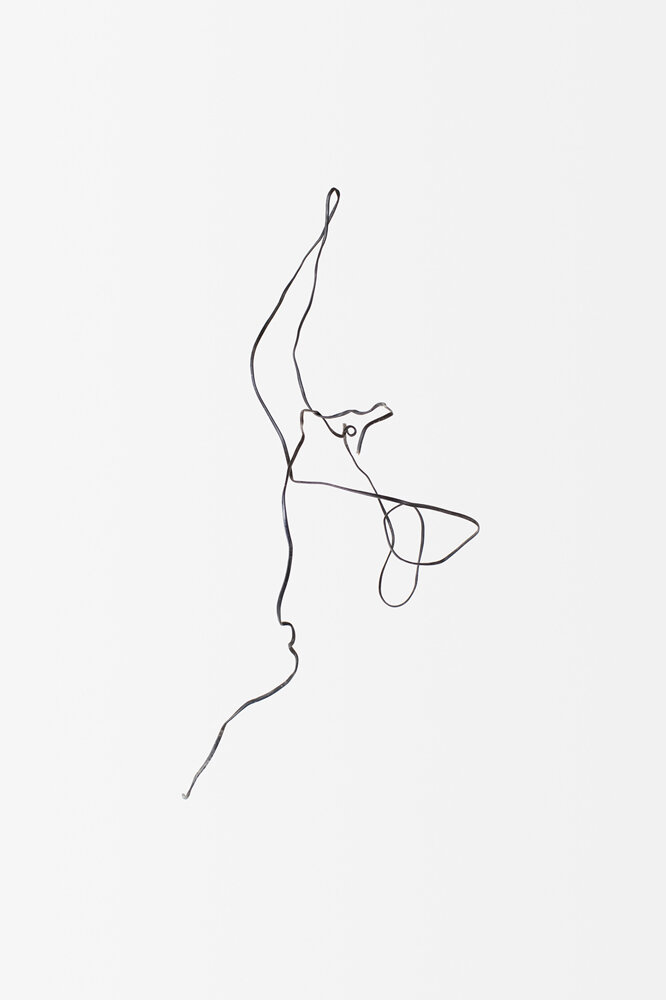

Tell us about your process. What reference or influence do you take from other mediums? What are the important elements of what you do? I rarely take inspiration from other photographers, as I tend to view painters and sculptors as my main source of reference. But rather than be inspired by visual imagery, I find that reading articles and listening to practitioners being interviewed really inspires my creative process. I found an incredible old book hidden in the library (as the spine was so small), entitled ‘Marcel Duchamp or the Castle of Purity,’ and within this book it said ‘in art the only thing which counts is form.’ This particular sentence sparked ideas that influenced my project greatly. And I also find listening to people talking about art or their own practise a fantastic source of inspiration from which a conversation can be made with my own work. I allow curiosity to play a huge role in my art, as I try to explore the balance between order and uncertainty. The visual dialogue created when dissimilar objects in my photographs coincide with each other, hopes to question what relationship they may have, if any at all. I recently read something by Camille Henrot that particularly resonates with me. That there ‘is too much expectation that the work should make sense… and that a certain balance is needed between what needs to be understood and what should remain unknown.’

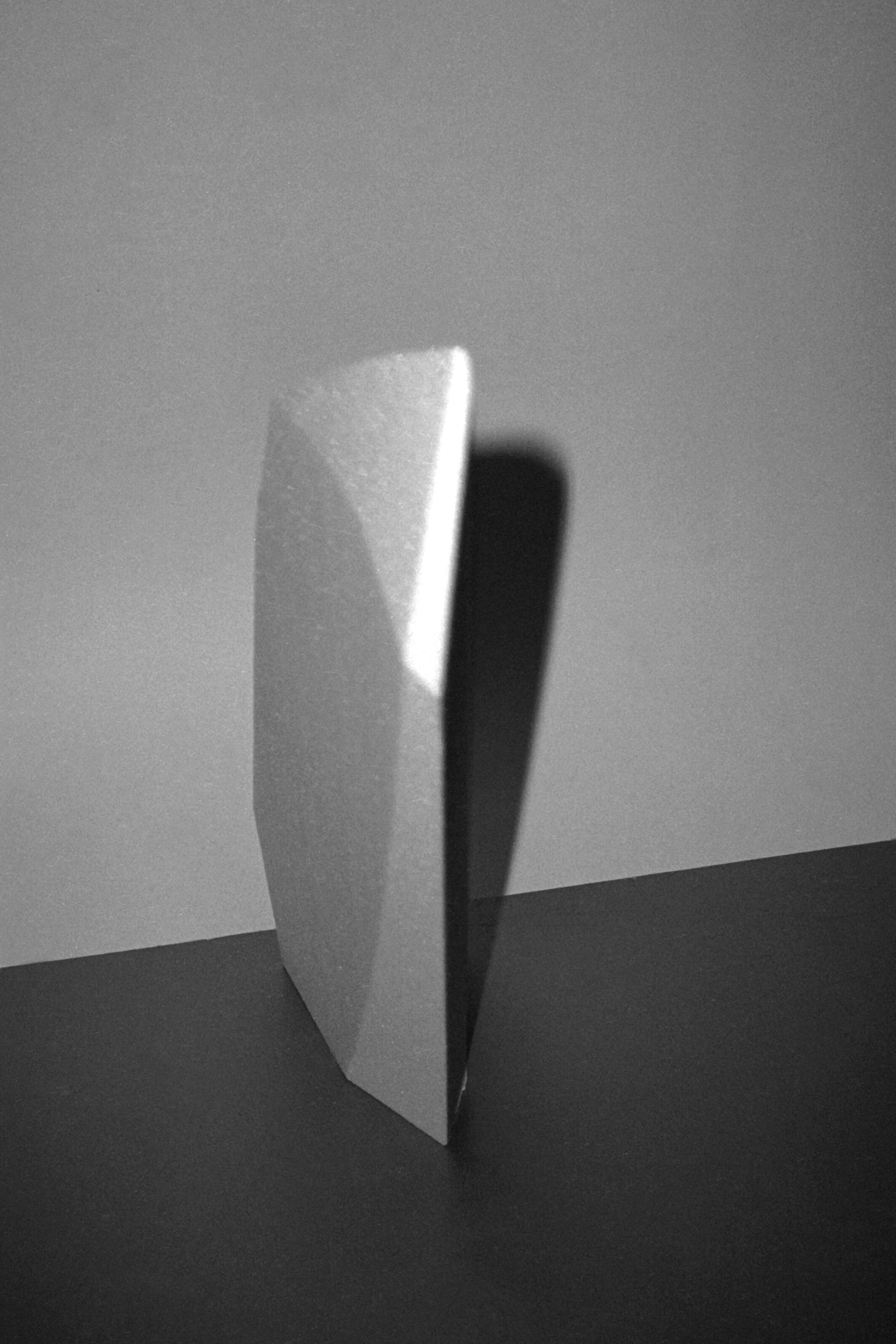

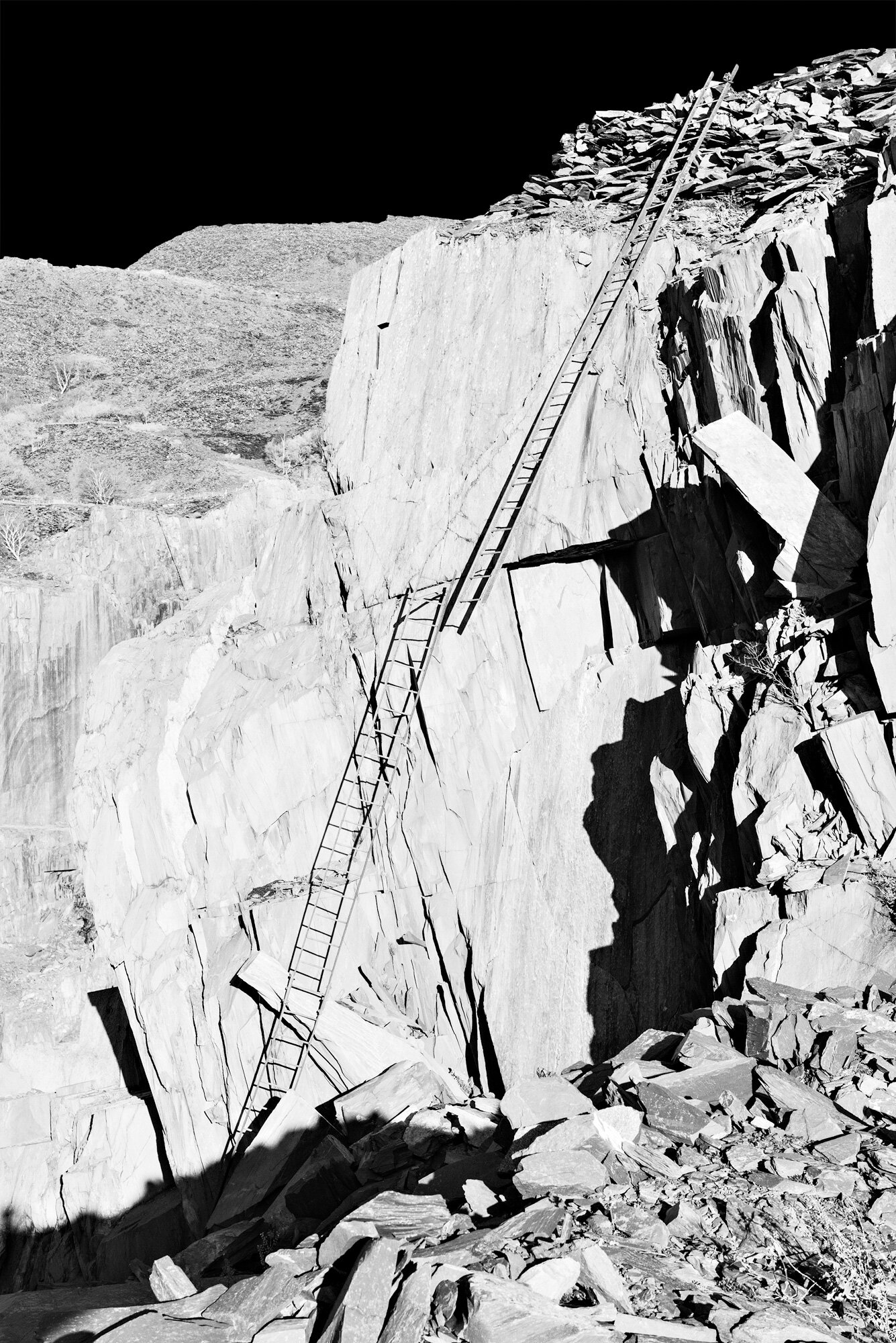

Are these pictures concerned with exploring formal and aesthetic interests, or are they representational, metaphorical? What is the weight that holds these pictures together? My practice enables me to explore the formal and spatial qualities of the photograph, whilst also considering the photograph as an object– a flat surface that could be manipulated and altered. By abstracting the forms within my photographs, I find myself able to make objects appear new and unfamiliar. This has allowed me to investigate the potential for the camera to transform an object into a piece of art and to ask whether an object needs to loose all aspects of functionality to considered artwork? I feel that the simple act of revealing the hidden structures of these mundane objects, and placing them within the confines of the gallery or studio space, ignites our hidden curiosity for the shapes rendered visible through this casting process, exposing a sensuous depth to our common ignorance.

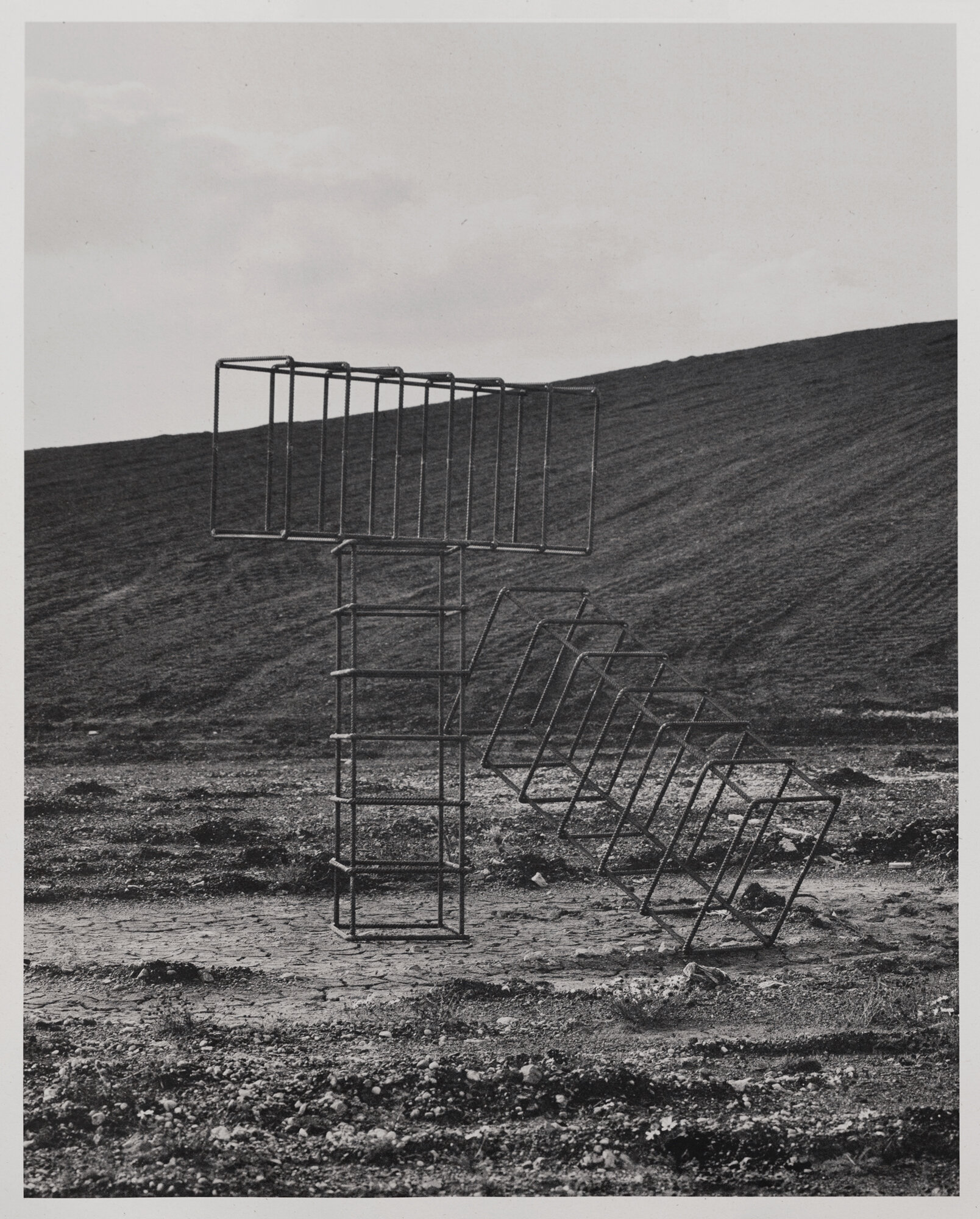

Are you a photographer or an artist using photography? I would say I have developed into an artist using photography to document my work, as I increasingly devote more and more time to the construction of the objects and sculptural forms I photograph. Using the camera to capture this moment of installation, enables the scenes to become deconstructed, leaving it up to the viewer to piece each element together.

Does your work reflect on the medium of photography or the photographic image? If so, is that intentional? By questioning the photograph as a physical object, I hope to address the significance of the printed image as an artifact. The title’s of my two most recent project’s: Temporary Sculpture and Accumulation, also reference the idea that the photograph does not need to be the final representation, and that it can be further questioned by being re-photographed. Through creating this new dialogue, we are able to gain an alternate perspective on the situation. The printed photograph can therefore result in a sculpture within itself.

Typically, are your works more about construction or deconstruction? I feel that I try to deconstruct the objects I portray in my installations in order to distance the viewers from all prior knowledge or associations they may have with that one thing. I can then construct the notion that the resulting work becomes something entirely different, establishing new and intentional functions. I tend to mix both found and new objects, to try to create a sense of confusion between the history of established objects and those, which have been distorted and manipulated. This relationship between the known and the unknown, prompts a conversation as to how we see an object we are familiar with, and how we interpret the function of an object when it is presented in a new way.

Are you interested in the notion of your pictures as objects? Do you think about how their physicality may endure as you are photographing them or is that an afterthought? I began to consider how photography has characteristics that flatten real, dimensional space down to a single plane and wanted to change the object itself, allowing it to become a new object entirely. As part of a recent project, I made concrete casts from small cardboard boxes– sculptural forms, which represent negative space; the area that was once a void inside each box. I later used the camera to document these works, abstracting the forms through my approach. From these images, I was able to digitally translate my interpretation of the concrete cast onto fabric, further removing the photograph from its original condition. I chose to transform this printed material into a domestic rug, as fabric implies a lack of stability and can alter quickly; giving a sense of tension between the real and the manipulated, thus challenging the viewer’s response to this newly perceptible state of my concrete interpretation. I applied the same principles of questioning the functionality of an object by digitally printing a section of fabric that represented the patterns and creases of a plastic bag. And with this particular piece, it was especially important for me to remove all previous preconceptions the viewer may have had towards the object; making it useless not in the sense of being without purpose, but without utility, or at least with not much of it. My compulsion to question this object, stemmed from the realisation that images are now a plastic medium in them selves. It was therefore possible to draw a tension between the final outcome of the photograph as either a reproduced piece of material or a printed photograph.

Often sculptural photographic works are concerned with elevating banal objects, situations or events to a status of ‘art’ – when does something become art for you? This particular question is constantly being asked throughout my work, as I utilise found and mundane objects in the installations that I create. I design and create objects such as chairs, rugs etc. based upon a chosen domesticated design that all viewers could recognise. But if a chair becomes translated as a sculpture in the confines of the gallery, then would you interact with the object if you were to see the chair outside the gallery? Donald Judd once stated that ‘we try to keep furniture out of art galleries to avoid this confusion’ of what is art and what is classed as a functional object? With this in mind, I feel the gallery context enables us to reassess the artifact in ways that we may not otherwise have realised, due to the familiarity and banality of the object in our everyday life. Michael Craig- Martin was conscious ‘that in a lot of art that used real objects, the one thing artists got rid of was usage,’ How does an object become art? The gallery draws our attention to the artifacts, as to see art being seen, gives viewers the idea to investigate exploration.’ I strongly relate to artists such as Donald Judd, Gavin Turk and Martino Gamper– all of whom allow the authorising status of the gallery to make their sculptural objects become pieces of artwork, ready for visual investigation and contemplation.